Reviewing Our Basic Anatomy

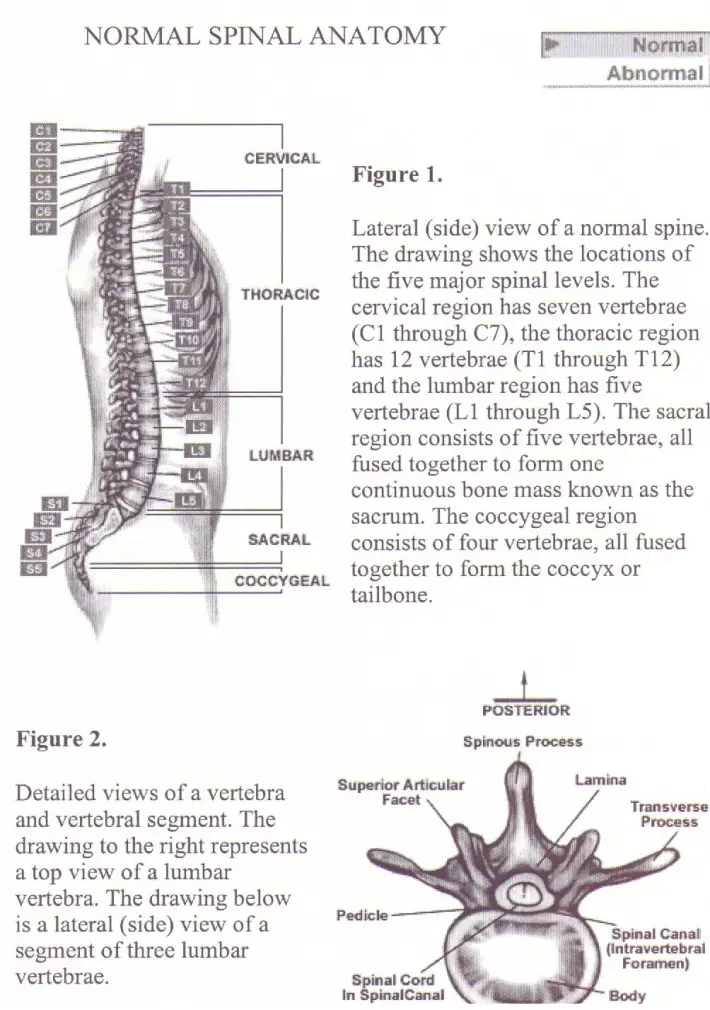

Let’s take a quick look at the biomechanics and anatomy of your spine (Figure 1.0).

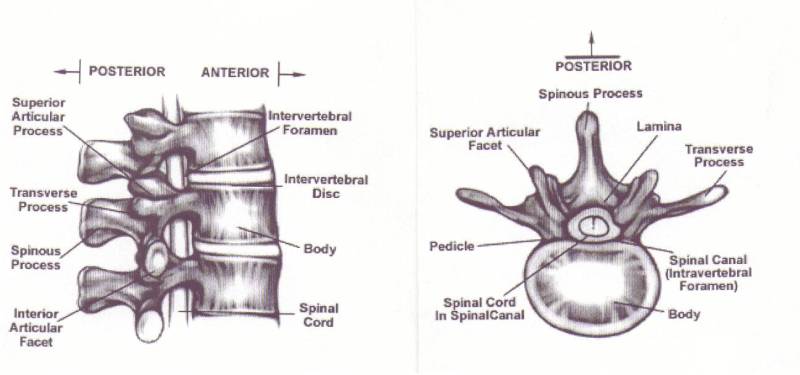

The front or anterior part of your spine is smooth and has a backward “C” shape. The back or posterior part of your spine has an added bone that comes off the back of the vertebra which is known as your spinous processes. Now in between each vertebra is a gel filled substance which acts as a shock absorber. The gel filled substance is called the nucleus pulposus. (Figure 1.1 & 1.2)

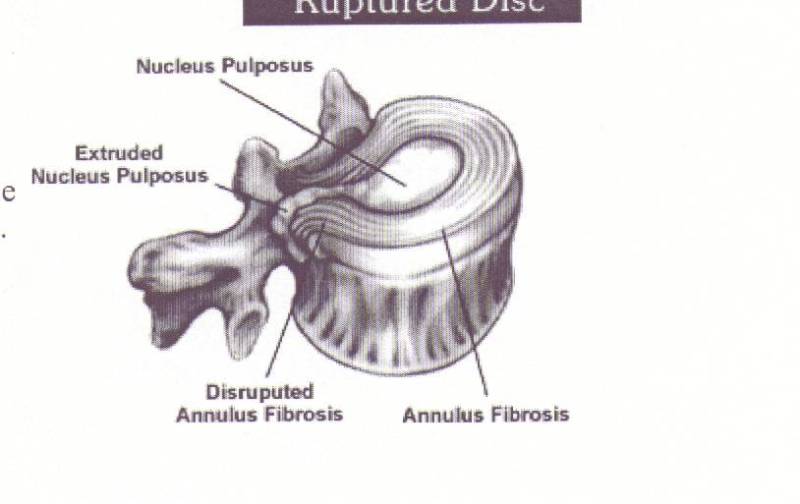

When someone hears the words disc herination or bulge it is the nucleus pulposus which has begun to leak out from the center of the disc and begins an inflammatory reaction around the outside nerve root. (Figure 1.3)

Nerve roots are apart of the spinal cord which exits out through the cord which exits out through the intervertebral foramen. Once nerve root exits out of the foramen it then subdivides into other nerves that supply the rest of our body both muscle and visceral innervations.

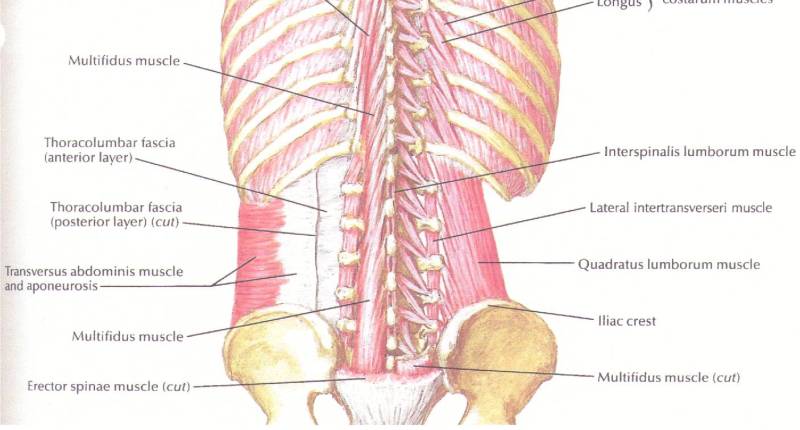

Most people do not realize that there are several smaller muscles that lie underneath our large superficial back muscles that have attachment points on the vertebral bodies and spinous processes. The muscles that attach to the vertebral bodies and the spinous processes are known as the semispinals, the multifidus, the interspinals, the intertransverarii and the rotators. These five smaller muscles provide stabilization and movement to your vertebral column, your spine. The movement these muscles produce is slight extension and/or rotation of the individual vertebra. (Figure 1.4)

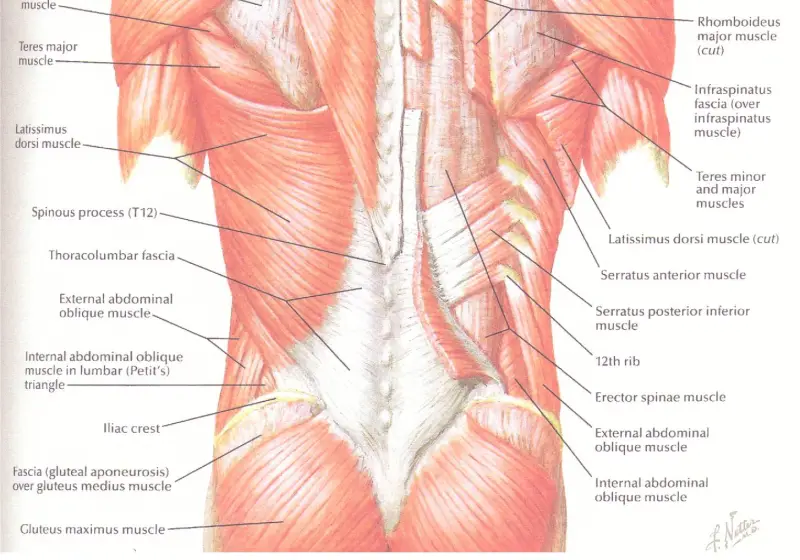

We are more familiar with the larger superficial muscles of the back such as the trapezius and the latissmus dorsi muscle. Now if we were to pull away the superficial muscle layer so we could see the next layer of muscle then we would see the erector spinae muscles. The erector spinae muscles lie in between the superficial and deep muscle layers. When we do abdominal exercises or exercises in general that might cause harm to our backs we think about utilizing the erector spinae muscles to protect our spine from being injured. The erector spinae muscles primary action is extension and adds greatly to trunk strength and stability. (Figure 1.5)

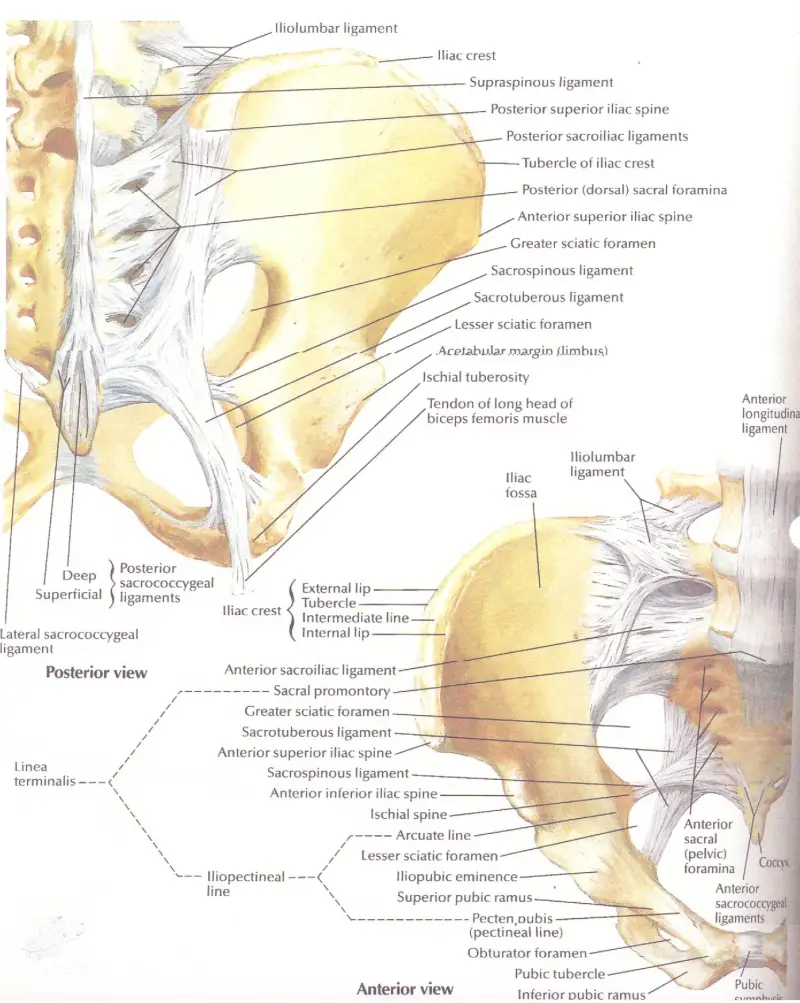

As mentioned before our core extends down to our pubic bone, which is part of your pelvic girdle. Our pelvis is made up of three bones: the pubic bone, the ilium, and the ischium. Now since we have a right and a left side, we have two pelvic bones that when connected form the pelvic girdle. On the ilium there is a smooth surface where the sacrum can attach and in between the two bones is a synovial filled capsule. (Figure 1.7)

The primary action of the pelvis is anterior and posterior movement. Even though the pelvic girdle is not part of the spine and has no connection with the abdominal muscles its role in core stabilization is vital.

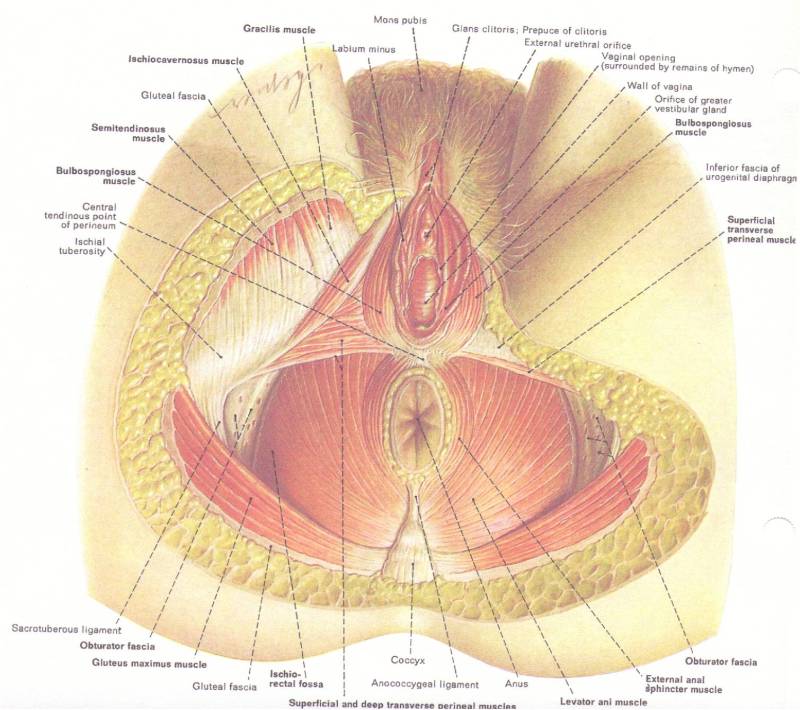

There are several muscles that make up the pelvic floor but mostly they are divided into two groups, the levator ani and urogenital diaphragm. The gluteus maximus is not a deep muscle of the pelvic girdle but it is one of the major superficial muscles of the pelvic floor. The main function of the gluteus maximus is hip extension when contracted. So when the muscle is put into a stretch position it allows the pelvis to rock posterior so the lumbar curvature may flatten when performing core exercises. Studies have shown that when core stabilization exercises are performed that there is a sufficient amount of muscle activity being elicited in the gluteus maximus demonstrating the muscle’s importance in core exercises. When we think about core stabilization we need to remember that our pelvic floor is the center of the core. Before we begin to contract our abdominal muscles our pelvic floor muscles need to contract first in order for a core stabilization exercise to be performed. (Figure 1.7)

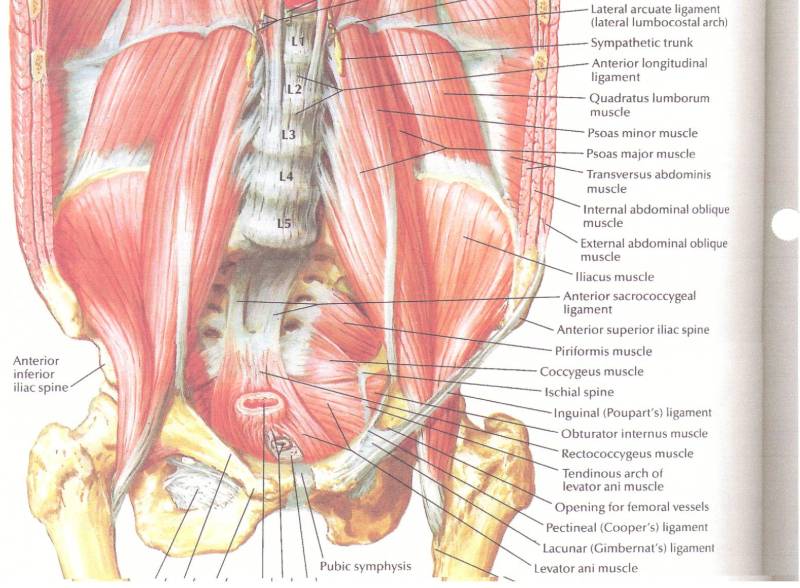

On the outer rim of the ilium there are two attachment points for the quadratus lumborum and the iliopsoas muscles. The psoas muscle attaches on the anterior vertebral bodies of L4, L3, L2 and L1 and inserts on the lesser trochanter of the femur. (Figure 1.8)

When combined these three muscles aid in stabilizing the spine but their primary function is hip flexion. Later on we will see how to test these muscles to see if they are strong or weak and how they help us with core stabilization exercises.

If you where to go up to your client or patient and say to them that you are going to train their core muscles they would probably wonder what you are talking about. But if you told them that you where going to do some abdominal exercises they would probably think “six pack”. The media has led us to believe that everyone needs to have a “six pack” in order to have trunk strength or better yet core strength. This is not true. Like I had mentioned before even athletes need to do core stability exercises in order to enhance their performance because it’s not about strength and power in the distal muscles (the muscles away from our center). Research has found through surface EMG (electromyography) studies that it is not the combination of the rectus abdominus and the external oblique abdominus muscles that strengthen our core but it is the transverses abdominus and internal oblique abdominus.

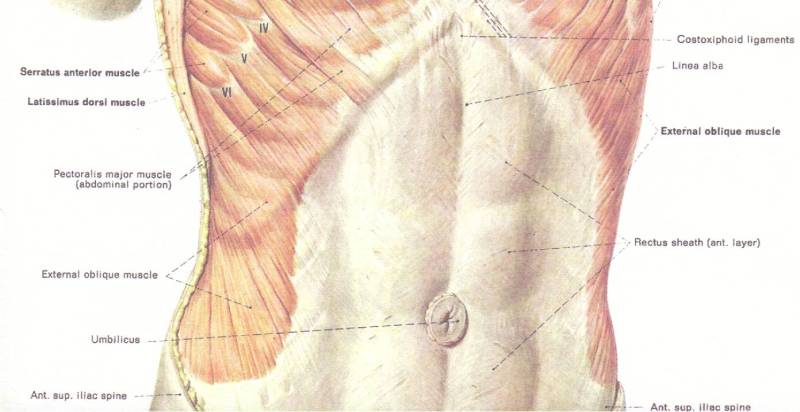

If we look at the general anatomy of the abdominal muscles (Figure 1.9) the superficial layer of muscle is made up of the rectus abdominus and external oblique abdominus. The rectus abdominus runs the length of your torso from under your breastbone to your pubic bone. The primary action of the rectus abdominus is trunk flexion. The external oblique abdominus is seen as being the “wings” of the abdomen because they run along the side of the abdomen on an oblique angle. The external oblique comes around from the posterior lower ribs and wraps its way around to the front where it attaches along the midline of the body. The primary action of the external oblique is side bending and rotation of the torso.

Now if we peel away the superficial layer and look at the deep muscles of the abdomen we would see the transverse abdominus and the internal oblique abdominus muscles (Figure 1.10).

The transverse abdominus muscle is the primary muscle used when we do core stabilization exercises. We can think of the transverse abdominus muscle as a giant belt because it wraps around our entire trunk and inserts on our spinal column. The primary action of the transverse abdominus is to compress the abdominal contents (organs) when we perform trunk flexion. The internal oblique abdominus muscle lies underneath the external oblique abdominus muscle but lies at a 90-degree angle. The primary action of the internal oblique abdominus is side bending as well as trunk flexion.

UNDERSTANDING GENERAL MOVEMENT

Now that we have a general understanding of the anatomy, understanding the general movement can become second nature. So if we were to bend at the waist flexing our spine, we would feel a contraction among our abdominals and a stretch among our erector spinae muscles. And if we where to extend our back, looking up at the ceiling, we would feel a stretch at our abdominals and a contraction throughout our back. Now let’s look at a rotational movement. Go ahead and sit in a chair that can not roll or slide. Place your feet on the floor in front of you so your legs are at a 90 degree position and then cross your arms over your chest. By sitting in the chair we are able to isolate spinal movement without involving the pelvic girdle. Now go ahead and twist to the right slowly and go as far as you can without hurting yourself. What you should feel is the opposite trunk wall muscles stretching, both the external obloquies and the posterior back muscles, while the same side contracts. When this is done go ahead and repeat the exercise to the opposite side and the same should happen.

But for now let’s look at what we already know by applying our understanding of movement and anatomy to a simple core stabilization exercise. Lie on the floor or mat with your knees bent and contract your pelvic floor. When learning to contract your pelvic floor muscles always think about stopping the flow of urine. Keep your pelvic floor contracted and flatten out our lower back, so it is touching the floor. As we flatten out our lower back our core stays tighten while our lower back muscles and hip flexors, e.g. Psoas and quadratus lumborum and erector spinae, begin to stretch while the transverse abdominus and internal oblique abdominus contracts. Then hold the position for five seconds and then relax.

Later we will add to this basic core exercise that will challenge our core muscles and your clients/patients core muscles. And for more information contact +Heather Gansel of Head-To-Toe Chiropractic.